Cardiac sarcoidosis is a topic that is growing in popularity both in research and among patients. New research is being published every week on the topic, and thanks to increased awareness and screening procedures, more patients and physicians are aware of the risk for cardiac sarcoidosis and are being proactive about assessing that risk and screening for it when appropriate.

FSR wanted to answer some of the most popular and pressing questions patients might have about cardiac sarcoidosis and enlisted the help of a cardiologist who specializes in sarcoidosis, Edward J. Miller, MD, PhD of Yale University School of Medicine. Below represents his opinions on these questions:

Before I delve into these questions, it is important to realize that cardiac sarcoidosis is a disease where the data and evidence behind our evaluation and treatment approaches is evolving rapidly and may be incomplete. For example, there has never been a published randomized, controlled clinical trial analyzing the different diagnostic and/or treatment strategies for cardiac sarcoidosis. Therefore, many of the decisions that we as physicians make about patients with suspected or known cardiac sarcoidosis are based on retrospective analysis, as well as expert opinion. Data on cardiac sarcoidosis has also evolved rapidly in the past decade or so as our imaging methods for cardiac sarcoidosis have improved. Therefore, I will try to answer two common questions by sharing my opinion and experience as a cardiac sarcoidosis specialist.

Question 1: “Do I have cardiac sarcoidosis?”

On the surface, this would seem to be an easy question to answer. However, the “gold standard” of heart biopsy for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis is rarely used due to the patchy nature of the disease as it affects the heart. For example, a heart biopsy sample is only a couple millimeters thick. If the biopsy misses an area of sarcoid during the biopsy procedure, then the disease could still be present in the heart but the biopsy just missed it.

There are number of clinical criteria that have been developed that assist physicians in making the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. These include the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare criteria as well as the Heart Rhythm Society criteria. These criteria are sometimes a useful place to begin one’s evaluation, but they frequently fail to provide diagnostic certainty to many patients who we as physicians think have the disease.

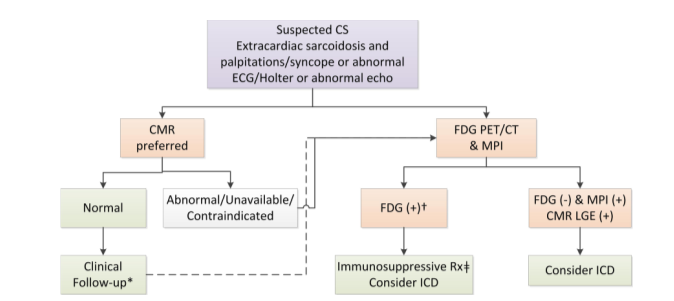

Therefore, many doctors are turning towards techniques that image the heart to look for signs and features of cardiac sarcoidosis. These include cardiac MRI scans and FDG PET scans. These scans look at different facets of sarcoidosis, such as scar and inflammation, respectively. I look at these scans as complimentary to each other and, in some cases, feel that both scans are necessary in order to understand a patient’s particular risk of having the disease. In my opinion, these scans are most effective in patients with a history of sarcoid outside of the heart as well as signs and/or symptoms (such as changes on the patient’s ECG) that are consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis.

In general, I think that if someone has evidence of sarcoid somewhere else in their body (such as the lungs), and has cardiac FDG PET and cardiac MRI scans that show classic features of cardiac sarcoidosis then there is a high likelihood of disease being present in the heart. However, a word of caution that these scans can be difficult to perform and interpret accurately. It is critical that they be performed in centers with expertise and interpreted by readers who understand the potential pitfalls and artifacts that can be present in the scans. If you ever go to see a new doctor about your cardiac sarcoidosis, please make sure to bring the disks of your prior scans with you so that they can review the images directly.

This chart is from a recent publication co-authored by Dr. Miller (Slart et al., JNC 2017.) It shows how cardiac MRI and FDG PET are complementary imaging approaches for the diagnosis and treatment and management of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.

Question 2: “Do I need treatment for my cardiac sarcoidosis?”

There are two mainstays of treatment for cardiac sarcoidosis. These include immunosuppression to decrease cardiac inflammation and potentially prevent progression of the disease, as well as implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) implantation which can protect patients from life-threatening consequences of heart rhythm problems.

Regarding immunosuppression, my practice is to consider immunosuppression in patients in whom I feel there is a high likelihood of cardiac sarcoidosis as well as FDG PET imaging findings showing heart inflammation. In my opinion, the goal of immunosuppression is to reduce the sarcoidosis inflammation in the heart. I use FDG PET scanning to monitor therapy, realizing we do not know the optimal regimen, intensity, and duration of immunosuppression. Indeed, in many cases we do not have data that shows us that immunosuppression has long-term benefits in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Nonetheless, there are small studies that suggest immunosuppression may improve and/or prevent worsening of heart function in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. There is also some data to suggest that immunosuppression may have some effect on reducing arrhythmias, but this evidence is more limited.

The decision to implant a defibrillator can be challenging because the devices, while beneficial in many cases, have certain long-term risks. Also, once they are implanted in a patient they are very rarely are taken out. In certain scenarios ICDs can be very helpful, including if the patient has survived a prior cardiac arrest, has severely reduced heart function, or also needs a pacemaker because their heart conduction system is not working correctly. More challenging cases are ones where the patient does not meet a “classical” indication for an ICD such as those described above. In the scenarios, I use markers that we believe are associated with high risks of heart arrhythmias, such as a lot of heart “scar” on cardiac MRI, arrhythmias on ECG monitoring, or other factors. In all cases, I think it is important for the physician and the patient to have a discussion about the implications of the ICD implantation and what it means for their long-term care, quality of life, and the risk-benefit that each individual patient is likely to derive from the ICD implantation.

The guideline documents for cardiac screening and therapy monitoring that Dr. Miller is referring to can be found at the links below:

If patients have questions about cardiac sarcoidosis or have other concerns about their disease, they should consult with their doctor or a sarcoidosis specialist. If you need help finding a doctor who is knowledgeable about sarcoidosis, try FSR’s online Physician Finder or contact us at info@stopsarcoidosis.org.

Information on this site or found through links on this site is never intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Please consult your healthcare provider about any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.